TSI visits the studio of English Sculptor Beth Cullen Kerridge in Marlow, England.

The English sculptor Beth Cullen Kerridge has been pushing the boundaries of her artistic medium for years. Her works embody a frenetic western life, carved out in bronze and marble. Everyday objects such as the suit, or a shirt and tie, have become reoccurring images in her work as she explores their meaning and what they represent to the culture—whether that be money, city life, or the relationship between men and their jobs. Of late her work has expanded into the realm of Gastroart—a new artistic concept which places art in new, non-gallery environments, reinventing pubs or restaurants as public art spaces. The concept, which was inspired by Kerridge’s work with her husband—the Michelin star chef Tom Kerridge—in his restaurants brings art to places where it wouldn’t normally be appreciated. The project has tackled many different themes of food, culture, and how people live their lives, and has recently inspired works by the photographer P. Gerard Barker, whose series Food for Thought features Kerridge and is on display in London’s West Contemporary Gallery.

Kerridge studied at John Moores University in Liverpool and at the Royal College of Art. She produced works for Eduardo Paolozzi, Elisabeth Frink, and Alberto Giacometti before becoming a studio assistant with Mike Bolus for Sir Antony Caro. Her vast catalog of commissions and exhibits include projects with Sir Norman Foster on the Millennium Bridge, Richard Roger, the Tate, and she has contributed works to the Venice Biennale. In 2017, she received the Global Art Award for Sculpture for the 16-foot marble sculpture, Dhow Sail, which was commissioned by the Dubai Opera. Her works have been seen at the public gallery space within London’s Corinthia hotel, in Grosvenor Square, and Brown Hart Gardens in Mayfair, and a piece for the Crossrail Gardens at Canary Wharf.

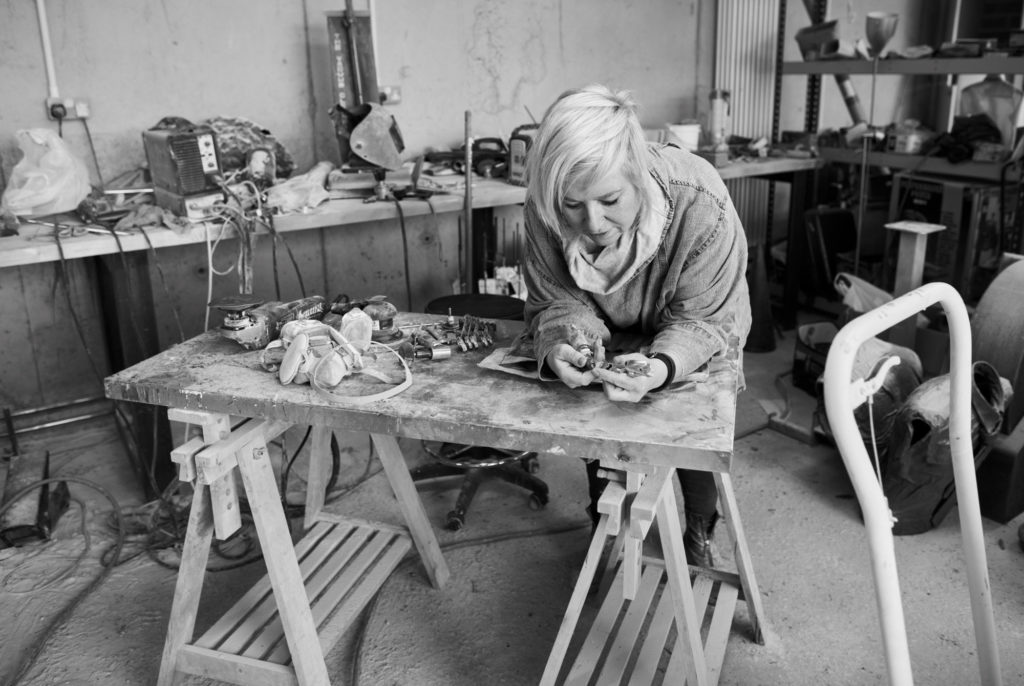

Earlier this year, photographer Trisha Ward photographed Kerridge in a series highlighting her artistic process at her studio in Marlow, England where Kerridge continues to work, alongside her husband and their partner, art curator and gallerist, Liam West, to make art more accessible to visitors and citizens of the United Kingdom.

What do you remember about the first time you held a sculpting tool in your hand?

I was brought up with tools around me, and as a kid my pops would always build things with us, whether it was a treehouse or a swing. He would hand me a massive hammer and enormous nail. I remember the visceral, sensory feeling of when we had made something—the smell of his workshop and the wood when we cut it. Though I admit, I am still rubbish with a hammer and nail. I think if I hadn’t been an artist, I would have loved to build houses. I do that on a small scale for the business, building them and renovating them. I really enjoy the process of making a space work and feel right. Like those early days building things with my dad, I turned to sculpture because I couldn’t help it. I love materials. Even today when the marble or bronze I am trying to work with feels like it is beating me, I get a kick out of working it into submission, and finding its beauty gives me a lot of joy. I also feel that I inspire a better conversation and tell a better narrative with sculpture than I do verbally. And I love the fact that it will probably outlive me, that is a privilege to leave behind a tiny legacy in our immense history.

“I love materials. Even today when the marble or bronze I am trying to work with feels like it is beating me, I get a kick out of working it into submission, and finding its beauty gives me a lot of joy.”

Where do you draw your work from? Are there particular themes or ideas that you are trying to explore?

I draw directly from life experience and what is happening or has happened to me or my family.

I also think I use the male and female form naturally, though I haven’t really dwelled on it too much until recently. I have begun using the female form in a lot of my new work as a way to celebrate women. I am humbled by the women who have paved the way before me, so I am using my artwork to try and exemplify that.

Why is humor so important to your work?

I do love to use humor sometimes. I think it is important to be cheeky, because life is too short and one needs to be able to have fun. Humor helps make it easier to deal with more dark and gritty subjects.

Do you think art today is accessible or approachable enough for people?

Art is accessible in so many places. And we should think of art as being whatever it needs to be—that’s the beauty of it. It can deal with any topic, it just needs to be in the right place for the right people. I do think that people have been intimidated with over intellectualized hogwash about art. Sometimes people will ask “so tell me what this particular work means.” When that happens, I ask them to first look at the piece and tell me what they see, just to provoke them a little and to open their eyes. I think it helps give them confidence to really see so they can then make up their own opinion. I think artists like Banksy have helped so much with pushing this concept and pushing people out of their comfort zones.

I read an interview about the Dhow Sail sculpture in Dubai and you stated that it was probably strange for visitors to Dubai’s opera house to see a young western woman creating this kind of artwork. Were you cognizant of this clash of cultures when making the piece?

The experience of working on the Dhow sculpture was incredible. First, it allowed me the opportunity to collaborate with my artisan friends in Italy, which was such a privilege and with who I find sublimely inspiring. And secondly, the opportunity to cut such an enormous block of marble was a truly emotional experience, and I felt as though I was playing a tiny part in history being written between western and UAE cultures. The work is meant to exemplify the values and foundation of Dubai and create a sense of calm and serenity while sitting in the shadow of the Burj Khalifa and echoing the aesthetics and ethos of the opera house.

You recently introduced a new art space to Kerridge’s Bar & Grill, a restaurant run by your husband. What was the main purpose in developing this project?

I love restaurants and great food, but they can easily become generic and boring. For Tom and myself, sculpture and food represent who we are, so it seemed obvious and exciting to combine both. My work in Kerridge’s reflects the beginning of our journey with our first restaurant The Hand and Flowers to our future working with West Contemporary. It’s Gastroart, which sounds like a great new concept to me!

You put aside your career for a while in order to help your partner succeed with his restaurant. What did you learn from this experience?

I did put my sculpture aside for a little while, but it was also necessary at the time, not just financially but also creatively. I had worked for many years for Sir Anthony Caro who I loved and learned an incredible amount from, but I ended up making really rubbish versions of his work. I just couldn’t help it. I had given so much to him that I mislaid my own aesthetic. So helping Tom was an easy change, and I was able to reignite my voice and begin sculpting again with my own vision.

“…I was able to reignite my voice and begin sculpting again with my own vision.”

Did you find working in food and in restaurants radically different than your own work, or were there parallels?

The aspect of working hard and long was the same to me, but in the restaurant, I didn’t have a product at the end and that bugged me. And I had to work in a team, whereas when I am sculpting, I am pretty much alone in my studio. I suppose that working something through, using your common sense was similar, but the day-to-day was completely different. I would prefer to be in my studio for sure!

In times of Trump politics, #metoo, and Brexit, young people are expressing their opinions more and more with strength and with new vision. Do you think art is a good channel to convey this change? Has the global political climate influenced your work at all?

I think that art is such a glorious field and can be many things at the same time. I love political art, one of my favorite painters is Philip Guston, particularly his work from the 60’s. I think that we can’t help but express the sign of our times through our work as artists. I feel it’s essential to be true to ourselves and our work, and the times and context will be evident—whether it is through the materials we use or the language or the images we adopt.

“I think that we can’t help but express the sign of our times through our work as artists.”

Do you think that art can change aspects of our rapidly changing world? What is your relationship with the passing of time?

Of course we can change the world, but we may need to do it together. If we can influence just one Greta Thunberg, then maybe that can help begin an avalanche of change. I love the thought of the legacy of a moment in time and the commemoration of stupendous humanity. It’s important to punctuate and comment on our time here on earth. I do hope we can work towards respecting our earth though and stop taking her for granted. This sculpture is formulating.

What would you say to your younger self?

Try to live in the now. And don’t regret anything you did not do.

In what ways does womanhood and motherhood inspire your art?

Being a woman in this world is a gift we just have to take! We have to be strong and make sure we enjoy it, take no prisoners, and keep forging towards equality.

I am a celebrating women in my next series of work. After having my son Acey, I realized just how amazing women have to be daily, how they have to dig deep and find enormous strength of character to be themselves, to be wives, mothers, all while succeeding in their careers. I am striving to glorify these evolved and fantastic beings.